Social Psychology:

- Finished 6-11.

This commit is contained in:

parent

647f5d03d5

commit

2ed4f3b3a1

127

PSYG2504 Social Psychology/06.md

Normal file

127

PSYG2504 Social Psychology/06.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,127 @@

|

|||||||

|

# 6. Persuasion

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> PSYG2504 Social Psychology

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 6.1 What is persuasion?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Effect to change others’ attitudes through the use of various kinds of messages.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

A symbolic process in which communicators try to convince other people to change their attitudes or behaviours regarding an issue through the transmission of a message in an atmosphere of free choice. (Perloff, 2010).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The process by which a message induces a change in beliefs, attitudes, or behaviours (Myers, 2005).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 6.2 Cognitive Theory of Persuation

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

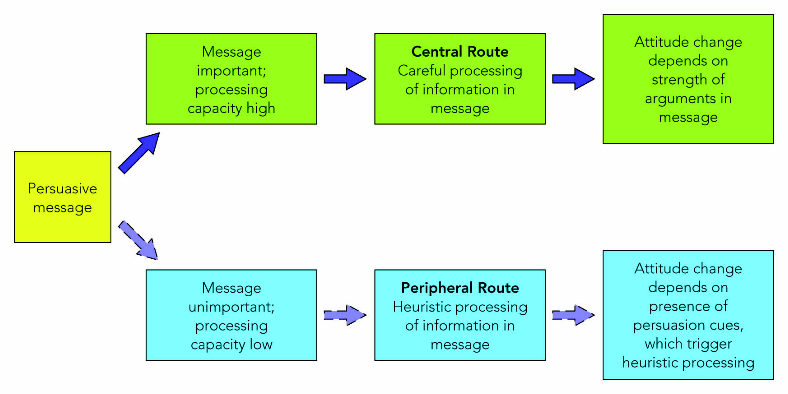

*Elaboration LIkeihood Model (“ELM”) by Petty, R. E. & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986).*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Aims to tell when people should be likely to elaborate, or not, on persuasive messages.

|

||||||

|

People can be simple as an information-processor or detailed, deep thinkers.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **Elaboration** – the extent to which the individual thinks about or mentally modifies arguments contained in the communication.

|

||||||

|

- **Likelihood** – the probability that an event will occur.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Systematic processing (central route to persuasion)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- The case in which people have the ability and the motivation to elaborate on a persuasive communication, listening carefully to and thinking about the arguments presented

|

||||||

|

- Involves considerable cognitive elaboration

|

||||||

|

- Requires effort and absorbs much of our information-processing capacity

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Heuristic processing (peripheral route to persuasion)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- The case in which people do not elaborate on the arguments in a persuasive communication but are instead swayed by more superficial cues

|

||||||

|

- Examine the message quickly and use of mental shortcuts

|

||||||

|

- Requires less effort

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 6.3 Elements of persuasion

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 6.3.1 The communicator (Who says)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Credibility

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*A credible communicator is perceived as both an expert and trustworthy.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **Perceived expertise**: knowledgeable on the topic

|

||||||

|

- **Speaking style**: speak confidently and fluently

|

||||||

|

- **Perceived trustworthiness**

|

||||||

|

Believing that the communicator is not trying to persuade (Hatfield & Festinger, 1962) – If you want to persuade someone, start with information, not arguments

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Attractiveness

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **Attractiveness**

|

||||||

|

Emotional arguments are often more influential when they come from people we consider beautiful.

|

||||||

|

Matter most when people are making superficial judgments.

|

||||||

|

- **Similarity**

|

||||||

|

We tend to like people who are like us.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 6.3.2 The message content (What is said)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Reason vs Emotion

|

||||||

|

*Well-educated or analytical audience: rational appeals (Cacioppo et al., 1983, 1996).*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **The effect of good feelings**: more persuasive when there is an association between the messages and good feelings.

|

||||||

|

Receiving money or free samples induces people to donate money or buy something.

|

||||||

|

- **Mood-congruent effects**: people tend to perceive everything positive when they are in a good mood.

|

||||||

|

Make faster, more impulsive decisions and rely more on peripheral cues.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*The effect of arousing fear– messages that evoke negative emotions in the recipient.*

|

||||||

|

Fear appeals – a persuasive communication that tries to scare people into changing attitudes by conjuring up negative consequences that will occur if they do not comply with the message recommendations (the more frightened and vulnerable people feel, the more they respond).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Discrepancy

|

||||||

|

*Cognitive dissonance – internal conflict between the attitudes and the behaviours that prompts people to change their attitudes/opinions.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### One-sided vs two-sided appeals

|

||||||

|

*The message looks fairer and more disarming if it recognizes the opposition’s arguments (Werner, 2002).*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

‘No aluminium cans please!’ vs ‘It may be inconvenient, but it is important!!!!!!’

|

||||||

|

Which do you think is more persuasive?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Primacy vs Recency

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Primacy effect – information presented first usually has the most influence

|

||||||

|

- Recency effect – information presented last sometimes has the most influence but less common than the primacy effect

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Carney & Banaji (2008)

|

||||||

|

Participants were presented two similar-looking pieces of bubble gum.

|

||||||

|

One placed after the other on a white clipboard.

|

||||||

|

62% chose the first-presented choice.

|

||||||

|

“First is best.”

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 6.3.3 The channel of communication (How is it said)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Persuasive speaker must deliver a message that can get attention, understandable, convincing, memorable and compelling.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The major influence on us is not the media but our CONTACT with people.

|

||||||

|

Media influence: Two-step flow – the process by which media influence occurs through opinion leaders (experts), who in turn influence others.

|

||||||

|

e.g. a father wants to evaluate a new mobile phone, he may consult his son, who get many ideas from what they read online.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 6.3.4 The audience (To whom is it said)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Age

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Generational explanation – the attitudes the elderly adopted when they were young persists and this makes a big difference from those being adopted by young people nowadays.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### The cognition of the audiences

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Forewarned is forearmed – prepare the counterarguments if the audience is forewarned (e.g. mock interview/examination).

|

||||||

|

- Distraction – distracting the attention can stop counterarguing.

|

||||||

|

- Uninvolved audiences use peripheral cues.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 6.4 How to resist persuasion?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 6.4.1 Strengthening personal commitment - Reactance

|

||||||

|

*A negative reaction to an influence attempt that threatens personal freedom .

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

We will feel annoyed and resentful when confronted with a persistent influence attempt.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 6.4.2 Forewarning

|

||||||

|

*Advance knowledge that one is about to become the target of an attempt at persuasion.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

As it activates several cognitive processes that are important for persuasion.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 6.4.3 Selective avoidance

|

||||||

|

*People’s tendency to filter out information that is inconsistent with their pre-existing attitudes.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Direct our attention away from information that challenges our existing attitudes.

|

||||||

|

E.g. mute the commercials, cognitively ‘tune-out’ when confronted with information that is opposite to our attitudes

|

||||||

186

PSYG2504 Social Psychology/07.md

Normal file

186

PSYG2504 Social Psychology/07.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,186 @@

|

|||||||

|

# 7. Conformity and compliance

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> PSYG2504 Social psychology

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 7.1 Compliance

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 7.1.1 What is compliance (遵守)?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Compliance increased even though the explanation provided no logical justification.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

“Mindless conformity”.

|

||||||

|

The response is made almost without thinking.

|

||||||

|

We spare the mental effort of thinking and simply comply with the situation.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Underlying Principles (Cialdini, 1994)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

1. **Friendship/liking** – we are willing to comply with requests from friends and from people we like.

|

||||||

|

2. **Commitment/consistency** - once committed to a position/action, more willing to comply with requests for behaviors that are consistent with the position/action.

|

||||||

|

3. **Reciprocity** - we feel compelled to pay back ; we are more likely to comply with a request from someone who has previously helped us.

|

||||||

|

4. **Scarcity** – we comply with requests that are scarce or decreasing in availability.

|

||||||

|

5. **Authority** – we comply with requests that are from someone who holds legitimate authority (obedience).

|

||||||

|

6. **Social validation** - We want to be correct: we act or think like others (conformity).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 7.1.2 Compliance techniques?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Technique based on liking Ingratiation

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

A persuasive technique that involves making the persuasive target like you in order to persuade them by

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Agreeing with them

|

||||||

|

- Flattering them

|

||||||

|

- Being nice to them

|

||||||

|

- But may backfire if the ingratiation is too obvious

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Techniques based on commitment or consistency

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

##### Foot-in-the-Door Technique

|

||||||

|

*First make a small request (usually so trivial that it is hard to refuse, e.g. free sample) and then follow with a larger request.*

|

||||||

|

It may not work if the first request is too small and the second request is too large

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Self-perception theory – the individual’s self-image changes (e.g. they are agreeable person) as a result of the initial act of compliance.

|

||||||

|

- Desire to be consistent – especially for those who express a strong personal preference for consistency.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

##### Door-in-the-Face Technique

|

||||||

|

*First make a large and unrealistic request before making a smaller, more realistic request.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Cialdini et al. (1975) stopped college students on the street and asked them to serve as unpaid counselors for juvenile delinquents 2 hours a week for 2 years (83% said no)

|

||||||

|

> Scaled down to a 2-hour trip to the zoo with a group of such adolescent (50% agreed!)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Techniques based on reciprocity

|

||||||

|

##### That’s-Not-All Technique

|

||||||

|

*First make a large request, then throwing in some ‘added extras’ to pressure the target to reciprocate (e.g. discount, bonus).*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Burger’s (1986) tried to sell one cupcake and two cookies for 75 cents to students on campus

|

||||||

|

> Control: a prepackaged (1 cupcake & 2 cookies) set for 75 cents

|

||||||

|

> Experimental: 75 cents for the cupcake and then 2 FREE cookies!

|

||||||

|

> Results: 40% Vs. 73%.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Persons on the receiving end view the “extra” as an added concession, and feel obligated to make a concession themselves.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

##### Playing Hard to Get Technique

|

||||||

|

*Suggesting a person or object is scarce and hard to obtain.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Commonly observed in the area of romance.

|

||||||

|

Shown to be effective in job hunting (William et al., 1993).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

##### Deadline Technique

|

||||||

|

*Targets are told that they have only limited time to take advantage of some offer or to obtain some items.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 7.1.3 How to resist compliance?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

**Reactance theory (Brehm, 1966):**

|

||||||

|

*A negative reaction to an influence attempt that threatens personal freedom*

|

||||||

|

*Bensley and Wu (1991).*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

studied anti-drinking messages of 2 intensities:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Strong: there is “conclusive evidence” of the harm of drinking and that “any reasonable person must acknowledge these conclusions”.

|

||||||

|

- Mild: there is “good evidence” and “you may wish to carefully consider” these findings.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

In a first study, average students reported that they intended to drink less in the coming few days after reading the mild message

|

||||||

|

In a second study, fairly heavy alcohol drinkers (college students) actually consumed more beer after reading the strong message

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 7.2 Obedience

|

||||||

|

### 7.2.1 What is obedience?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*An extreme form of social influence involved changing your opinions, judgments, or actions because someone in a position of authority told you to.*

|

||||||

|

Obedience is based on the belief that authorities have the right to make requests.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 7.2.2 Milgram’s experiment

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Milgram was interested in the point at which people would disobey the experimenter in the face of the learner’s protests.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Method

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- The learner mentions that he has a slightly weak heart

|

||||||

|

- You control an electric shock machine

|

||||||

|

- When he is wrong, you have to punish him: first by “15 Volts - Slight Shock” and in the end, “450 Volts - XXX”

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Sample of the learner’s schedule of protests (recording)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- 75V: Ugh!

|

||||||

|

- 165V: Ugh! Let me out! (Shouting)

|

||||||

|

- 270V: (Screaming) Let me out of here (3 times). Let me out. Do you hear? Let me out of here.

|

||||||

|

- 285V: (Screaming)

|

||||||

|

- 315V: (Intense screaming) I told you I refuse to answer. I’m no longer part of this experiment.

|

||||||

|

- (No more sound in the end)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The experiment’s script

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Please continue.

|

||||||

|

- The experiment requires that you continue.

|

||||||

|

- It is absolutely essential that you continue.

|

||||||

|

- You have no other choice; you MUST go on.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Disscussion

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- imagine you are in Yale Univ. Psy. Dept.

|

||||||

|

- the experiment is about the effect of punishment on learning

|

||||||

|

- You and another person are teacher and learner

|

||||||

|

- You have to read aloud pairs of words that the learner has to memorize

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The Milgram experiments illustrate what he called the “normality thesis”.

|

||||||

|

The idea that evil acts are not necessarily performed by abnormal or “crazy” people.

|

||||||

|

He also succeeded in illustrating the power of social situations to influence human behavior.

|

||||||

|

His findings were replicated in different countries (e.g., Jordan, Germany, Australia) and with children as well as adults (e.g. Shanab & Yahya, 1977).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 7.2.3 Determinants of obedience

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Emotional distance of the victim

|

||||||

|

When the victim is remote and the ‘teachers’ heard no complaints, all teachers obeyed calmly to the end.

|

||||||

|

But when the learner was in the same room, ”only” 40% obeyed to 450 volts.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Closeness and legitimacy of the authority

|

||||||

|

When the experimenter is physically close to the ‘teachers’, the compliance increases (if by phone, only 21% fully obeyed).

|

||||||

|

Given that the experimenter must be perceived as the authority or legitimate.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Institutional authority

|

||||||

|

The reputation/prestige leads to the obedience.

|

||||||

|

#### The liberating effects of group influence

|

||||||

|

Milgram placed two confederates to help to conduct the experiment.

|

||||||

|

Both confederates defied the experimenter.

|

||||||

|

The real participant did not continue the experiment.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 7.3 Conformity

|

||||||

|

### 7.3.1 What is conformity?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*The desire to be accepted and to avoid rejection from others leads us to conform.*

|

||||||

|

Conformity due to normative influence generally changes public behavior but not private beliefs.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

e.g. speak politely in front of me but swear among the classmates/friends

|

||||||

|

However, through dissonance reduction, a behavioral change can lead to a change in beliefs

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 7.3.2 Asch’s experiment?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Subjects’ task was to pick the line on the left that best matched the target line on the right in length.

|

||||||

|

> Alone, people virtually never erred. But when four or five others before them gave the wrong answer, people erred about 35% of the time. 75% of subjects conformed at least once.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 7.3.3 Why conform?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Others’ behavior often provides useful information.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Trust in the group affects conformity

|

||||||

|

- Task difficulty affects conformity

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

**Informational Influence**: The Desire to Be Right

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

**Normative Influence**:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **The Desire to Be Liked**

|

||||||

|

- **Norm**: an understood rule for accepted and expected behavior; prescribes “proper” behavior.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 7.3.4 When conform?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

1. **Group Size**

|

||||||

|

The larger the group, the more conformity—to a point (beyond 5 would diminish returns).

|

||||||

|

Gerard et al. (1968) found that 3-5 people elicit more conformity than just 1-2 people.

|

||||||

|

2. **Group Unanimity**

|

||||||

|

Even one dissenter dramatically drops conformity (Allen & Levine, 1969).

|

||||||

|

3. **Status**

|

||||||

|

People of lower status accepted the experimenter’s commands more readily than people of higher status.

|

||||||

|

4. **Cohesion **

|

||||||

|

A “we feeling”.

|

||||||

|

The more cohesive group is, the more power it gains over its members.

|

||||||

|

5. **Public response**

|

||||||

|

People conform more when they must respond in front of others rather than writing their answers privately.

|

||||||

123

PSYG2504 Social Psychology/08.md

Normal file

123

PSYG2504 Social Psychology/08.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,123 @@

|

|||||||

|

# 8. Behaviors in Group

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> PSYG2504 Social Psychology

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 8.1 What is group?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Two or more people who interact and are interdependent in the sense that their needs and goals cause them to influence each other.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 8.1.1 Why do people join groups?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Allow us to accomplish objectives that would be more difficult to meet individually.

|

||||||

|

- A substantial survival advantage to establishing bond with other people.

|

||||||

|

- Help us define who we are (i.e. identity).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 8.1.2 Behaviour in the Presence of others

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Any differences of your behavior when you are doing it alone and performing in front of others? (Singing in the bathroom Vs singing in public?).

|

||||||

|

- The presence of others sometimes enhances and sometimes impairs an individual’s performance

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

In summary: whether social facilitation or social loafing occurs depends on

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Whether individuals are identifiable.

|

||||||

|

- Task complexity.

|

||||||

|

- How much participants care about the outcome.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 8.2 Social Facilitation

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

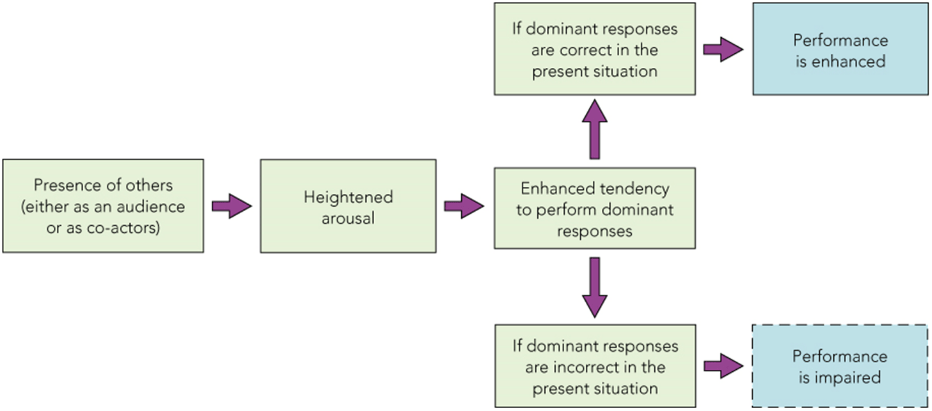

*When people are in the presence of others and their individual performances can be evaluated, the tendency to perform better on simple tasks and worse on complex tasks.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> **Michaels et al. (1982)**

|

||||||

|

> Studied pool players in a college student union building.

|

||||||

|

> Pairs of players who were above or below average were identified and scores were secretly recorded.

|

||||||

|

> Teams of 4 confederates approached the players.

|

||||||

|

> Poor players: accuracy dropped from 36 to 25%.

|

||||||

|

> Good players: accuracy rose from 71 to 80%.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> **Michaels et al. (1982)**

|

||||||

|

> Studied pool players in a college student union building.

|

||||||

|

> Pairs of players who were above or below average were identified and scores were secretly recorded.

|

||||||

|

> Teams of 4 confederates approached the players.

|

||||||

|

> Poor players: accuracy dropped from 36 to 25%.

|

||||||

|

> Good players: accuracy rose from 71 to 80%.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 8.2.1 Drive Theory of Social Facilitation/Inhibition (ZAJONC ET AL., 1969)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **Mere presence:**

|

||||||

|

The presence of others make us more alert. The alertness causes mild arousal.

|

||||||

|

- **Evaluation Apprehension**: (Cottrell, Wack, Sekerak & Rittle, 1968)

|

||||||

|

You feel as if the other people are evaluating you.

|

||||||

|

- **Distraction**: (Baron, 1986)

|

||||||

|

The conflict produced when an individual attempts to pay attention to the other people present and to the task being performed.

|

||||||

|

It is difficult to pay attention to two things at the same time as the divided attention produces arousal.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Social facilitation and social inhibition occur when a person’s performance can be evaluated both by the individual and by observers.

|

||||||

|

What would happen if the contributions of each member of a group could not be evaluated individually?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 8.3 Social Loafing

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*When people are in the presence of others and their individual performances cannot be evaluated, the tendency to perform worse on simple or unimportant tasks but better on complex or important tasks.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

When an individual’s contribution to a collective activity cannot be evaluated, individuals often work less hard than they would alone.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 8.3.1 Collective Effort Model (CEM) (Karau and Williams; 1993, 1995)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Social loafing depends on

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- How important the person believes his/her contribution is to group success.

|

||||||

|

- How likely that better performance will be recognized and rewarded.

|

||||||

|

- How much the person values group success.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Social loafing will be weakest when

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- they expect their coworkers to perform poorly.

|

||||||

|

- individuals work in small rather than big groups.

|

||||||

|

- they perceive that their contributions to the group product are unique and important.

|

||||||

|

- they work on tasks that are intrinsically interesting.

|

||||||

|

- when they work with respected others, e.g. friends.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 8.3.2 Reducing Social Loafing

|

||||||

|

- Make each person’s contribution identifiable.

|

||||||

|

- Provide rewards for high group productivity.

|

||||||

|

- Make task meaningful, complex, or interesting.

|

||||||

|

- A strong commitment to the ‘team’.

|

||||||

|

- Keep work groups small.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 8.3.3 Social compensation

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Occurs when a person expends great effort to compensate for others in the group.*

|

||||||

|

When others are performing inadequately, and the person cares about the quality of the group product.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 8.3.4 Other Factors

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Gender

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Stronger in men than in women (Karau & Williams, 1993)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Women tend to be higher in relational interdependence, i.e. focus on and care about personal relationships

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Cultures

|

||||||

|

- Stronger in Western cultures than Asian cultures (Karau & Williams, 1993).

|

||||||

|

- Social loafing has been found in India, Thailand, Japan, Malaysia and China.

|

||||||

|

- People in collectivistic culture value group achievement more.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 8.4 Deindividuation

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*The loosening of normal constraints on behavior when people can’t be identified (such as when they are in crowd).*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> **Diener et al. (1976)**

|

||||||

|

> Researchers stationed at 27 homes waiting for children who were trick-or-treating on Halloween.

|

||||||

|

> IV1: anonymous (no name asked) or identified (names asked).

|

||||||

|

> IV2*: alone or in groups.

|

||||||

|

> Children were given an opportunity to steal extra candy when the adult was not present.

|

||||||

|

> Those children who have been asked names (identified) were less likely to steal.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Deindividuation increases when individuals are anonymous and as group size increases*.

|

||||||

|

Make people feel less accountable for their actions when they recognize there is a reduced likelihood that they can be singled out and blamed for their behavior (Zimbardo, 1970).

|

||||||

|

Increases obedience to group norms (Postmes & Spears, 1998).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Does not always lead to aggressive or antisocial behavior, it depends on what the group norm is.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Deindividuation online: People feel less inhibited about what they write because of their anonymity.

|

||||||

176

PSYG2504 Social Psychology/09.md

Normal file

176

PSYG2504 Social Psychology/09.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,176 @@

|

|||||||

|

# 9. Interpersonal Attraction

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> PSYG2504 Social Psychology

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Why people like or dislike each other.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Human beings have the need for affiliation (i.e. association with others).

|

||||||

|

The motivation to interact with others in a cooperative way.

|

||||||

|

We want to have close ties to people who care about us.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 9.0.1 Attraction: Basic Principles

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- We like people **who like us**: self-esteem

|

||||||

|

- We like people **who satisfy our needs**: love, safety, money, sex…

|

||||||

|

- We like people **when the rewards they provide outweigh the costs** (social exchange theory)

|

||||||

|

- The analysis of relationships in terms of rewards and costs people exchange with each other

|

||||||

|

- We also make judgments, assessing the profits we get from one person against from another

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 9.0. 2 Sex Differences in Mate Selection

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- For both sexes, characteristics such as kindness and intelligence are necessities

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Men rank physical attractiveness higher (Feingold, 1990; Jackson, 1992)

|

||||||

|

Women were more willing than men to marry someone who was NOT “good-looking” (Sprecher et al., 1994)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Women places financial resources higher

|

||||||

|

- Men prefer younger partners, while women prefer older partners

|

||||||

|

- Applicable to many other cultures (Buss, 1989)

|

||||||

|

- Evolutionary explanation

|

||||||

|

Young and physically attractive are cues to women’s health and fertility (Johnson & Franklin, 1993)

|

||||||

|

- Social cultural explanation

|

||||||

|

Traditional distinct social roles: Men as the bread-winners; Women were economically dependent and poorly educated than men

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 9.1 Proximity

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*The best single predictor of whether two people will be friends is how far apart they live.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> **Back et al. (2008)**

|

||||||

|

> Randomly assigned students to seats at their first-class meeting.

|

||||||

|

> Each student made a brief self-introduction to class.

|

||||||

|

> One year after this one-time seating assignment…

|

||||||

|

> Students reported greater friendship with those who happened to be seated next to or near them during the first-class meeting.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 9.1.1 Why does proximity have an effect?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Availability: more chances to know someone nearby

|

||||||

|

- Anticipation of interaction:

|

||||||

|

We prefer the person we expected to meet

|

||||||

|

Anticipatory liking (expecting that someone will be pleasant and compatible) increases the chance of forming a rewarding relationship

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 9.1.2 The mere (repeated) exposure effect

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Simply being exposed to a person (or other stimulus) tends to increase liking for it.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> **Moreland & Beach (1992)**

|

||||||

|

> 4 equally attractive assistants silently attended a large Social Psychology lecture for 0, 5, 10 or 15 times.

|

||||||

|

> Students were asked to rate these assistants.

|

||||||

|

> Results?.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 9.1.3 Limits to Mere Exposure

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Most effective if stimulus is initially viewed as positive or neutral.

|

||||||

|

- Pre-existing conflicts between people will get intensified, not decrease, with exposure.

|

||||||

|

- There is an optimal level of exposure: too much can lead to boredom and satiation (Bornstein et al., 1990).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 9.2 Similarity

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

We like others who are similar to us in attitudes, interests, values, background & personality.

|

||||||

|

Applicable to friendship, dating and marriage.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

In romantic relationships, the tendency to choose similar others is called the matching phenomenon.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

People tend to match their partners on a wide variety of attributes .

|

||||||

|

Intelligence level, popularity, self-worth, attractiveness (McClintock, 2014; Taylor et al., 2011).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 9.2.1 Why do people prefer similar others?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Similar others are **more rewarding**.

|

||||||

|

e.g. agree more with our ideas or share activities

|

||||||

|

- Interacting with similar others minimizes the **possibility of cognitive dissonance**.

|

||||||

|

To like someone and disagree with that person is psychologically uncomfortable.

|

||||||

|

- We expect to **be more successful with similar others**.

|

||||||

|

Even we all like to date someone who is attractive, rich, and nice…

|

||||||

|

But having a similar partner provides basis for relationships that have higher chance to survive and mutually desired.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 9.2.2 Limits to Similarity

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Differences can be rewarding.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Differences allow people to pool-shared knowledge and skills to mutual benefit.

|

||||||

|

e.g. a Social Psy group project

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Similarity vs. Complementarity (Does opposite attract?).

|

||||||

|

People are more prone to like and marry those whose needs, attitudes, and personalities are similar (Botwin et al., 1997; Rammstedt &Schupp, 2008).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 9.2.3 Reasons or Results?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Proximity causes liking: Once we like someone, we take steps to be close

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Similarity causes liking and liking increases similarity

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Gruber-Baldini et al. (1995) followed married couples over a 21-year period.

|

||||||

|

Spouses were similar in age, education, and mental abilities at the initial testing.

|

||||||

|

Over time, they actually became more similar on several measures of mental abilities.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 9.3 Desirable personal attributes

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

There are large individual and cross-cultural differences in the characteristics that are preferred.

|

||||||

|

Within the U.S., the most-liked characteristics are those related to *trustworthiness*

|

||||||

|

*Including sincerity, honesty, loyalty and dependability*.

|

||||||

|

Two other much-liked attributes are personal warmth and competence *(Anderson, 1968)*.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 9.3.1 Warmth

|

||||||

|

*People appear warm when they have a positive attitude and express liking, praise, and approval (Folkes & Sears, 1977).*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Nonverbal behaviors such as smiling, watching attentively, and expressing emotions also contribute to perceptions of warmth (Friedman, Riggio, & Casella, 1988)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 9.3.2 Competence

|

||||||

|

*We like people who are socially skilled, intelligent, and competent.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The type of competence that matters most depends on the nature of the relationship.

|

||||||

|

e.g. social skills for friends, knowledge for professors

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 9.3.3 “Fatal Attractions”

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*The personal qualities that initially attract us to someone can sometimes turn out to be fatal flaws to a relationship.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- e.g. the “fun-loving” boyfriend who is later dismissed as “immature”.

|

||||||

|

- e.g. the professional success and self-confidence boyfriend who is later dismissed because he is a “workaholic”.

|

||||||

|

- About 30% of breakups fit this description (Felmlee, 1995, 1998).

|

||||||

|

- It is also found that “fatal attractions” are more common when an individual is attracted to a partner by a quality that is unique, extreme, or different from his or her own.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 9.4 Physical attractiveness

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Other things being equal, we tend to like attractive people more (Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986).*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> A meta-analysis found that although both men and women value attractiveness, men value a bit more **(Feingold, 1990)**.

|

||||||

|

> Gender difference was greater when men’s and women’s attitudes were being measured than when their actual behavior was being measured.

|

||||||

|

> Men are more likely than women to say that physical attractiveness is important.

|

||||||

|

> For actual behavior, men and women are fairly similar in how they respond to physical attractiveness.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*One reason we like more attractive people is that they are believed to possess good qualities.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Physically attractive people do not differ from others in basic personality traits, e.g. agreeableness, extraversion, or emotional stability (Segal-Caspi et al., 2012).

|

||||||

|

Attractive children and young adults are somewhat more relaxed, outgoing, and socially polished (Feingold, 1992).

|

||||||

|

Self-fulfilling prophecy – Attractive people are valued and favored, so many develop more social self-confidence .

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 9.4.1 “Benefits” of Attractiveness

|

||||||

|

Physically attractive people are more likely to

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- People of above-average looks tend to earn 10% to 15% more than those of below-average appearance (Judge, Hurst, & Simon, 2009).

|

||||||

|

- College professors perceived as attractive receive higher student evaluation ratings (Rinolo et al., 2006).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 9.4.2 Who is Attractive?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Culture plays a large role in standards of attractiveness.*

|

||||||

|

However, people do tend to agree on some features that are seen as more attractive: (Cunningham, 1986).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **Childlike features**: large, widely spaced eyes and a small nose and chin - “cute”.

|

||||||

|

- **Mature features** with prominent cheekbones, high eyebrows, large pupils, and a big smile.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 9.4.3 Good news for the plain people

|

||||||

|

To be really attractive, to be perfectly average (Rhodes, 2006): Statistically “average” faces are seen as more attractive (Langlois and Roggman, 1990).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

We not only perceive attractive people as likable, we also perceive likable people as attractive.

|

||||||

|

Gross and Crofton (1977) found that after reading description of people portrayed as warm, helpful, and considerate, these people looked more attractive.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 9.4.4 Why does attractiveness matter?

|

||||||

|

- Biological disposition

|

||||||

|

- Year-old infants prefer attractive adults, and they spend more time playing with attractive dolls than with unattractive dolls (Langlois et al., 1991).

|

||||||

|

- According to evolutionary theory, attractiveness may provide a clue to health and reproductive fitness (e.g. Kalick et al., 1998).

|

||||||

|

- Psychological schema

|

||||||

|

- People believe attractiveness is correlated with other positive characteristics.

|

||||||

|

- Social psychological influence

|

||||||

|

- Being associated with an attractive other leads a person to be seen as more attractive him or herself.

|

||||||

|

- “radiating effect of beauty”

|

||||||

248

PSYG2504 Social Psychology/10.md

Normal file

248

PSYG2504 Social Psychology/10.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,248 @@

|

|||||||

|

# 10. Altruism

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> PSYG2504 Social Psychology

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 10.1. Definitions

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

***Prosocial Behavior**: Any act performed with the goal of benefiting another person*.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

***Altruism**: The desire to help another person even if it involves a cost to the helper*.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 10.3 Why do we help?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

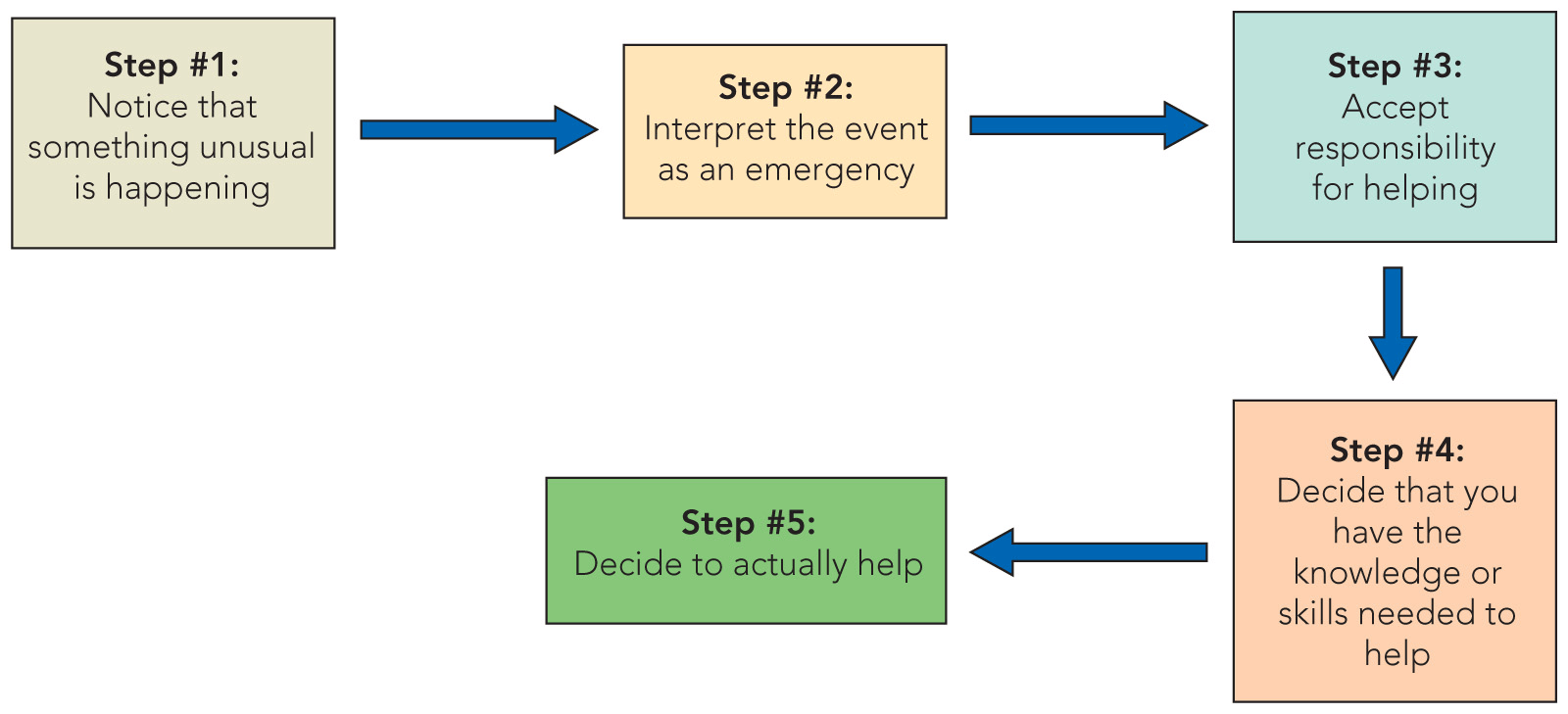

### 10.3.1 A decision-making perspective (Latané & Darley, 1970)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*People decide whether or not to offer assistance based on a variety of perceptions and evaluations.*

|

||||||

|

Help is offered only if a person answers “yes” at each step.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Notice the event

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

When we are distracted or in a hurry, we don’t help.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Correctly interpreting an event as an emergency

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Cues that lead us to perceive an event as an emergency (Shotland & Huston, 1979).*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Event is sudden & unexpected

|

||||||

|

- Clear threat of harm to a victim

|

||||||

|

- Harm will increase unless someone intervenes

|

||||||

|

- Victim needs outside assistance

|

||||||

|

- Effective intervention is possible

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> **Clark and Word (1972)**

|

||||||

|

> Heard maintenance man fell off a ladder and cried out.

|

||||||

|

> Alternative condition: without verbal cues that the victim was injured

|

||||||

|

> Help was offered only about 30% of the time.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Deciding that it is your responsibility to help

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Being given responsibility increases helping.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> **Moriarity (1975)**

|

||||||

|

> Radio at the beach

|

||||||

|

> Control: 20%

|

||||||

|

> Experimental: 95%

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Deciding that you have the knowledge or skills to act

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

In emergencies, decisions are made under high stress and sometimes even personal danger.

|

||||||

|

Well-intentioned helpers may not be able to give assistance or may mistakenly do the wrong thing.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Crammer et al. (1988)

|

||||||

|

> When there is an accident and possible: injury, a registered nurse is more likely to help than non-medical people.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Weighing the Costs and Benefits

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

At least in some situations, people weigh the costs and benefits of helping

|

||||||

|

People sometimes consider the consequences of NOT helping.

|

||||||

|

However, in other cases, helping may be impulsive and determined by basic emotions and values rather than by expected profits.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 10.3.2 A sociocultural perspective

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Human societies have gradually evolved beliefs or social norms that promote the welfare of the group.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **Norm of Social Responsibility**

|

||||||

|

Help those who depend on us.

|

||||||

|

e.g. parents, teachers, doctors.

|

||||||

|

- **Norm of Reciprocity**

|

||||||

|

Help those who help us (Gouldner, 1960).

|

||||||

|

- **Norm of Social Justice**

|

||||||

|

Maintain equitable distribution of rewards.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 10.3.3 A learning perspective

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### We learn to be helpful through reinforcement.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Children help and share more when they are reinforced for their helpful behavior.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> **Fischer (1963)**

|

||||||

|

> 4-year-olds more likely to share marbles with another child when they were rewarded with bubble gum for their generosity.

|

||||||

|

> (Dispositional praise) ‘You are a very nice and helpful person’ vs. (Global praise)‘That was a nice and helpful thing to do’.

|

||||||

|

> Dispositional praise appears to be more effective than global praise.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### We learn to be helpful through observation.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Children and adults exposed to helpful models are more helpful.

|

||||||

|

For children, helping may depend largely on reinforcement and modeling to shape behavior, but as they get older, helping may be internalized as a value, independent of external incentives.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 10.3.4 Attribution

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*We are more likely to be empathetic and to perceive someone as deserving help if we believe that the cause of the problem is outside the person’s control.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Myer & Mulherin (1980)

|

||||||

|

> College students would be more willing to lend rent money to an acquaintance if the need arose due to illness rather than laziness.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 10.4 Who helps?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 10.4.1 Mood and Helping

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*People are more willing to help when they are in a good mood.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Money: found coins in a pay-phone (Isen & Simmonds, 1978)

|

||||||

|

- Gift: been given a free cookie at the college library (Isen & Levin, 1972)

|

||||||

|

- Music: have listened to soothing music (Fried & Berkowitz, 1979)

|

||||||

|

- Odor: smelled cookies or coffee (Baron, 1997)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Mood-maintenance hypothesis

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*“Doing good” enables us to continue to feel good.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Good moods increase positive thought

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Limitation of the effect of good mood

|

||||||

|

“Feel good” effect is short-lived

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Only 20 minutes in one study (Isen, Clark, & Schwartz, 1976)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Negative moods sometimes lead to more helping

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

***Negative-state relief model** suggests that people may help as a way to make themselves feel better (Cialdini, Darby, & Vincent, 1973).*

|

||||||

|

Helping made college students feel more cheerful and feel better about themselves (Williamson & Clark, 1989).

|

||||||

|

When people feel guilty, they are more willing to help (Baumeister, Stillwell, & Heatherton, 1994).

|

||||||

|

Helping others may reduce their guilty feelings.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

***More valid for adults** (e.g. Aderman & Berkowitz, 1970) and **less valid for children** (e.g. Isen et al., 1973).*

|

||||||

|

Less likely to occur if a person is focused on themselves and their own needs

|

||||||

|

e.g. during profound grief (e.g. Aderman & Berkowitz, 1983).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 10.4.2 Empathy

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Empathy refers to feelings of sympathy and caring for others.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The emotional reactions that are focused on or oriented toward other people and include feelings of compassion, sympathy and concern.

|

||||||

|

Occurs when we focus on the needs and the emotions of the victim.

|

||||||

|

Fosters altruistic helping.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 10.4.3 Personality Characteristics

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

There is no single type of “helpful person”.

|

||||||

|

The effect of personality on altruism

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Individual differences in helpfulness persist over time

|

||||||

|

- People high in positive emotionality, empathy, and self-efficacy are most likely to be helpful

|

||||||

|

- Influences how people react to particular situations, i.e. people who are more sympathetic to the victim in emergency situations respond faster

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 10.5 Whom do we help?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 10.5.1 Gender

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Men are more likely to provide help to women in distress (e.g. Latané & Dabbs, 1975), especially when there is an audience.

|

||||||

|

- Men offered more help to women while women are equally helpful to both sexes (Eagly & Crowley, 1986).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Women are more likely to offer personal favors for friends and to provide advice on personal problems (Eagly & Crowley, 1986).

|

||||||

|

- Women provide more social support to others (Shumaker & Hill, 1991).

|

||||||

|

However, men more readily help attractive than unattractive women (e.g Mims et al., 1975).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Motivation may be romantic or sexual.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Przybyla (1985)

|

||||||

|

> Undergraduate men watched video

|

||||||

|

> Experimental: erotic/Control: nonsexual

|

||||||

|

> Situation: a female research assistant “accidentally” knocked over a stack of papers

|

||||||

|

> Experimental group more helpful than control

|

||||||

|

> 6 minutes compared with control with male (30 seconds)

|

||||||

|

> Female participants

|

||||||

|

> No difference between experimental and control

|

||||||

|

> No difference between male or female research assistant

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 10.5.2 Physically attractive

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Benson, Karabenick, and Lerner (1976).

|

||||||

|

> Subjects found a completed and ready-to-mail application to graduate school in a telephone booth at the airport

|

||||||

|

> Sample: 442 males and 162 females

|

||||||

|

> IV: photo attached belongs to an attractive or unattractive male/female

|

||||||

|

> DV: will they mail it for him/her?

|

||||||

|

> Results?

|

||||||

|

> Attractive: 47%

|

||||||

|

> Unattractive: 35%

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 10.5.3 Similarity

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Emswiller, Deaux, and Willits (1971)

|

||||||

|

> Confederates dressed as a ‘hippie’ or ‘conservative’

|

||||||

|

> Approached both ‘hippie’ and ‘conservative’ students to borrow a dime for phone call

|

||||||

|

> Results

|

||||||

|

> Fewer than half the students did the favor for those dressed differently from themselves

|

||||||

|

> Two-thirds helped those dressed similarly

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 10.6 When do we help?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

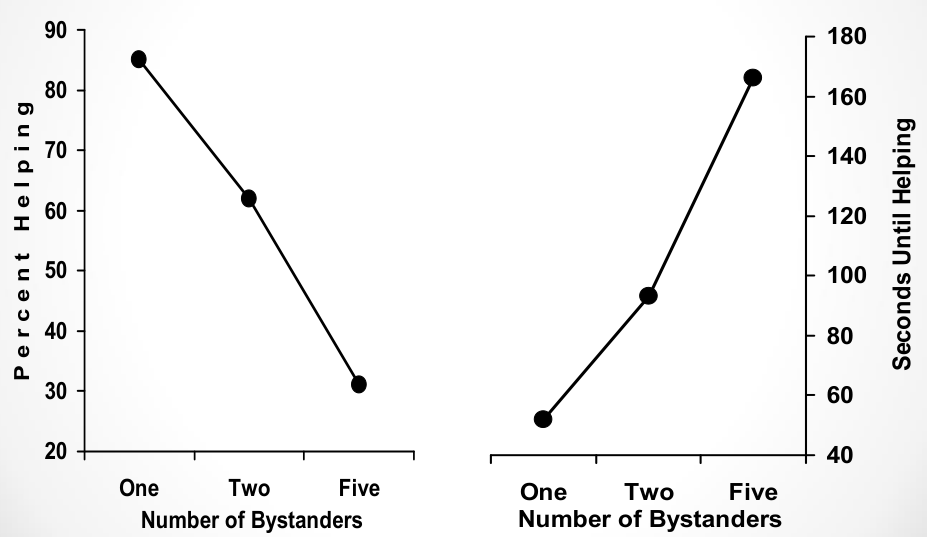

### 10.6.1 Bystander effect

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*The presence of other people makes it less likely that anyone will help a stranger in distress.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Kitty Genovese murder sparked research of Darley and Latané (1968)

|

||||||

|

> Male students in a study of “campus life”

|

||||||

|

> Sat alone and talked to another student through intercom

|

||||||

|

> Emergency: this fellow student said he sometimes had seizures and he soon began to choke, had difficulty speaking, and said he was going to die and needed help. Then, no more sound

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Darley and Latané (1968)

|

||||||

|

> IV: number of bystanders: 1, 2, 5

|

||||||

|

> Some students believed that they were the only person aware of the emergency

|

||||||

|

> In fact, he heard a recording and there was no bystander

|

||||||

|

> Only the way to help was to leave the lab and sought for that fellow student

|

||||||

|

> DV1: % of students left and helped

|

||||||

|

> DV2: time they waited before acting

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Why does the bystander effect occur?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

1. **Diffusion of responsibility **

|

||||||

|

*The presence of other people makes each individual feel less personally responsible.*

|

||||||

|

If only bystander, bear the guilt or blame for nonintervention

|

||||||

|

Assume the others ‘will do it’.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

2. **Pluralistic ignorance **

|

||||||

|

*Bystanders’ false assumption that nothing is wrong in an emergency because of others.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

3. **Evaluation apprehension**

|

||||||

|

Concern about how others are evaluating us

|

||||||

|

We try not to appear silly/cowardly in reacting to ambiguous situation (e.g. smoke filled room)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Latané and Darley (1968) pumped smoke into a research room where participants were doing questionnaire

|

||||||

|

> IV: alone in the room or with 2 confederates

|

||||||

|

> DV: the duration of leaving the room and reporting

|

||||||

|

> Result

|

||||||

|

> Alone: 1st minute: about 35% stopped and went out to report; 6th minute: 75%

|

||||||

|

> Group: 1st minute: 10%; 6th minute: 38%

|

||||||

|

> The behavior of other bystanders can influence how we define the situation and react to it

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 10.6.2 Environmental Conditions

|

||||||

|

People are more helpful to strangers when it’s pleasantly warm and sunny (Ahmed, 1979).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

People are more likely to help strangers in small towns & cities than in big cities (Levine et al., 1994).

|

||||||

|

What matters is current environmental setting, not the size of the hometown in which the person grew up.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 10.6.3 Time pressure

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Darley & Batson, 1973

|

||||||

|

> Participants were students studying religion and were asked to give a short talk

|

||||||

|

> IV1: Some were told to hurry, others to take their time

|

||||||

|

> IV2: assigned topic was either the Bible story or future job opportunities

|

||||||

|

> Results

|

||||||

|

> IV1: 63% of those not in a hurry vs. 10% in a hurry helped a coughing and groaning stranger they passed

|

||||||

|

> IV2: no difference

|

||||||

|

> Time pressure particularly caused students to overlook the needs of the victim.

|

||||||

153

PSYG2504 Social Psychology/11.md

Normal file

153

PSYG2504 Social Psychology/11.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,153 @@

|

|||||||

|

# 11. Aggression

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> PSYG2504 Social Psychology

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 11.0 Definition of Aggression

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Aggression is defined as intentional behavior aimed at causing either physical or psychological pain.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Aggression is a behavior and should be distinguished from feelings of anger.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Hostile aggression: stemming from feelings of anger with the goal of inflicting pain or injury

|

||||||

|

- Instrumental aggression: a means to achieve some goal other than causing pain

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 11.1 Roots of Aggression

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- **Biology** plays a role in human aggression.

|

||||||

|

People injected testosterone become more aggressive (Moyer, 1983)

|

||||||

|

reducing ability to control impulses.

|

||||||

|

- **Family environment** also greatly influences the expression of aggression (Miles & Carey, 1997).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 11.1.1 Social-cognitive learning theory

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- A main mechanism that determines aggression is past learning (Miles & Carey, 1997)

|

||||||

|

- As with other learned behaviors, aggression is influenced by both imitation and reinforcement

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 11.1.2 Freud

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Freud suggested that we have an instinct (thanatos) to aggress.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Evolutionary psychologists argue that physical aggression is genetically programmed into men:

|

||||||

|

To establish dominance over other males and secure the highest possible status.

|

||||||

|

Aggress out of sexual jealousy to ensure that their mate is not having sex with other men, thereby ensuring their own paternity (Buss, 2004, 2005)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 11.2 Social Determinants of Aggression

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 11.2.1 Provocation (挑衅)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Actions by others that tend to trigger aggression in the recipient, often because they are perceived as stemming from malicious intent.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Can be verbal or physical attack.

|

||||||

|

An “eye for an eye” reaction.

|

||||||

|

We tend to reciprocate, especially if we are certain that the other person meant to harm us.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 11.2.2 Frustration (挫折)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Anything that block the goal attainment.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Berkowitz (1989, 1993) proposed a revised version:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Frustration is an unpleasant experience.

|

||||||

|

- The experience leads to negative feelings.

|

||||||

|

- The negative feelings lead to aggressive behavior.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Frustration only produces anger or annoyance and a readiness to aggress if other things about the situation are conducive to aggressive behavior.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Includes family conflicts, job and money problems.

|

||||||

|

Dollard et al. (1939) proposed the famous frustration-aggression hypothesis

|

||||||

|

The theory that frustration triggers a readiness to aggress.

|

||||||

|

Now we know aggression is definitely NOT an automatic response to frustration.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 11.2.3 Displaced Aggression

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*When aggressive feelings cannot be expressed against the cause of the anger, we may engage in displaced aggression against a substitute target (Dollard et al., 1939).*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The more similar a target is to the original source, the stronger the aggressive impulse, but also the greater the anxiety that is felt about aggressing.

|

||||||

|

Displaced aggression is most likely to be directed towards targets that are weaker & less dangerous.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 11.2.4 Norms

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Social Norms are crucial in determining what aggressive habits are learned.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

e.g. norms for children of two sexes.

|

||||||

|

e.g. wars, sports.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 11.2.5 Media

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Various kinds of evidence are able to link media violence to aggressive behavior.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

1. **Modeling **

|

||||||

|

2. **Desensitization effect**

|

||||||

|

As a result of exposure to large amounts of violent content in TV programs, films, games, individuals become less sensitive to violence and its consequences (Anderson et al., 2003)

|

||||||

|

3. **Priming **

|

||||||

|

Hostile thoughts come to mind more readily, and this in turn, can increase the likelihood that a person will engage in overt aggression (Anderson, 1997)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 11.3 Cognitive Determinants of Aggression

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 11.3.1 Schema

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Reinforcement, imitation, and assumptions about others’ motives may all combine to produce a schema for aggression.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

When the schemas for aggression combine with the biological processes (e.g. physiological arousal), there is a high likelihood for aggressive behavior.

|

||||||

|

Media may contribute to the development and maintenance of these schemas (Huesmann, Moise, & Podolski, 1997)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

e.g. scripts for aggression

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 11.3.2 Attribution

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

For an attack or frustration to produce anger and aggression, it must be perceived as intended to harm.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Attributions of controllability affect this assessment.

|

||||||

|

Imagine someone steps on your heel and when you look back you see…

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 11.4 Situational Determinants of Aggression

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 11.4.1 Heat

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Psychologists now believe that heat does increase aggression, but only up to a point (Bell, 1980; Rule & others, 1987). *

|

||||||

|

When people get hot, they become irritable and may be more likely to lash out at others (especially when they have been provoked).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Beyond a certain level, aggression may actually decline as temperatures rise.*

|

||||||

|

People may become so uncomfortable and fatigued that they are actually less likely to engage in overt aggression.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 11.5 Reducing Aggressive Behavior

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 11.5.1 Catharsis

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

*Catharsis refers to Freud’s idea that the release of anger would reduce subsequent aggression.*

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Sports and shouting can reduce emotional arousal stemming from frustration (Zillmann, 1979).

|

||||||

|

- Watching violent media cannot (Geen, 1998).

|

||||||

|

- Attacking inanimate objects cannot (Bushman et al., 1999).

|

||||||

|

- Playing violent video games increases aggressive thoughts and behaviors (Anderson & Dill, 2000).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|